Getting away with murder in the city of St. Francis

No

justice in 3 out of 4 homicides; killers at large

One

year ago, a young mother was stabbed to death in her Richmond

district apartment by a former boyfriend in front of her two

children. Now her mother asks for one thing — justice.

“I

want the police to catch him. I want justice for my daughter,”

Clara Tempongko, the mother of the victim, told approximately 20

family members and supporters who gathered Oct. 22 for a vigil in

front of her daughter’s 22nd Avenue apartment.

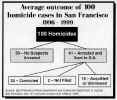

But

justice is something that occurs in only 25 percent of homicide

cases in San Francisco.

According

to statistics obtained from the homicide unit of the SF Police

Department and the California department of justice, police make

arrests in 41 percent of homicide cases and the District Attorney

convicts 61 percent of those arrested.

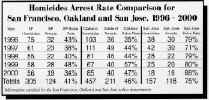

San

Francisco’s arrest rate lags behind the neighboring cities of

Oakland (46 percent) and San Jose (75 percent), cities with similar

populations (58 percent) and falls 17 percent below the national

average (67 percent).

The

Richmond District mirrors the citywide arrest rate, with seven

homicides committed between 1996 and 2000 that resulted in two

arrests and one warrant being issued for a suspect.

A

closer look at the criminal justice system reveals that many factors

contribute to the dismal picture: An over-worked homicide unit, the

reluctance of witnesses to come forward in gang-related homicides,

an under-staffed crime laboratory that is months behind producing

critical reports, a Crime Scene Investigations team so under-staffed

that it could compromise evidence, a District Attorney’s Office

that only prosecutes “rock-solid cases,” according to some

officials, and a slow, out-dated computer system.

San

Francisco Mayor Willie Brown recently cited the Tempongko murder as

an example of why the criminal justice system needs a new computer

system. The new system is designed so critical information can be

shared easily between the police, sheriff, District Attorney,

courts, and state and federal agencies.

Ironically,

one month before her death on Oct. 22, 2000, Clair Joyce Tempongko,

28, called police twice to her apartment to report that her

ex-boyfriend, Tari Ramirez, had choked and threatened her.

Copies

of the police reports never made it to the district attorney’s

office and the Adult Probation Department. When Ramirez went before

a judge for an unrelated incident last September, he could have been

sentenced to jail for a parole violation if the judge had been made

aware of the recent incidents.

Instead,

Ramirez was sentenced to 30 days in a work alternative program and

then he went after Tempongko. Police now believe Ramirez has fled to

Mexico.

Experts

familiar with San Francisco’s criminal justice system expressed

surprise at the low arrest, or “solve” rate.

“The

low solve rate on homicides shocks me,” said Linda Klee, the

criminal trial chief attorney for SF District Attorney Terence

Hallinan.

Peter

Keane, dean of the Golden Gate University Law School and chief

assistant San Francisco public defender from 1979 to 1998,

concurred.

“That

sounds very low to me,” Keane said. “Homicides are the category

of crime that is the most solvable.”

When

asked to comment on the low arrest rate, Mayor Brown, through his

press secretary, referred all questions to Police Chief Fred Lau.

Lau declined our request for an interview and referred all questions

to his public relations spokesperson, Dewayne Tully.

Tully

blamed the low arrest rate, in part, on the lack of cooperation by

witnesses in gang and drug-related shootings.

“Since

a disproportionately high number of gang and drug-related shootings

have recently contributed to the number of homicides and because

witnesses in such killings are historically reluctant to come

forward, many of these killings remain unsolved,” Tully said.

Tully

also said the statistics do not account for homicides that are

eventually solved.

“All

I can tell you is that homicide solving goes beyond investigators

following a step-by-step procedure that, at the end of a set period

of time, yields a suspect,” he said.

But

Tully’s remarks fail to explain why the city of Oakland, which is

known for its historically high number of gang and drug-related

shootings, does a better job of solving its homicide cases. While

Oakland’s homicide unit recently had the same number of

investigators and a much higher number of homicides that San

Francisco, its arrest rate is higher — 46 percent versus 41

percent.

At

the other end of the spectrum is San Jose. This Bay Area city, which

also has a high number of gang and drug-related homicides, has about

one-half the homicides and until recently three more investigators

that San Francisco. It also has a 75 percent arrest rate.

Witness

reluctant to come forward in gang-related cases

Last

year, when a number of shootings erupted in the Hunters Point/Bayview

community between rival street gangs, the SFPD brought 34-year

veteran homicide Inspector Napoleon (Nap) Hendrix out of retirement

to help solve a backlog of “cold cases.”

Last

year, when a number of shootings erupted in the Hunters Point/Bayview

community between rival street gangs, the SFPD brought 34-year

veteran homicide Inspector Napoleon (Nap) Hendrix out of retirement

to help solve a backlog of “cold cases.”

The

department is banking on the goodwill and trust Hendrix has built up

over the years with the African-American community and new

DNA-identification technology recently acquired by the city’s

crime laboratory to solve gang-related homicides that now languish

in file drawers.

But

just how many unsolved homicide cases there are in those file

drawers remains a mystery. Even Capt. Roy Sullivan, who heads up the

police department’s homicide unit, did not know.

“I

really couldn’t say. I don’t have an exact number. Homicides

cases from years back remain open until they are solved,” Sullivan

said.

Sullivan

did say that several new investigators were recently added to the

homicide unit, bringing the staff up to 13. The unit is still down

one from its traditional number of 14. Sullivan said the heavy

workload was a major cause for getting the additional officers.

“Our

unit was fatigued because of the caseload. We were concerned about

burnout,” he said.

Sullivan

also stressed that when gang members are involved in homicides,

members of the gang often help hide the suspect from the police or

give them money to leave town. He said it is not unusual for gang

members to flee to another large city where they can blend into the

population and escape detection.

Police

believe this may have happened two years ago when an argument over a

game of pool at a local watering hole in the Outer Sunset District

led to the murder of an innocent bystander, Robert Sadler.

Gang-related

homicide shocks Sunset

Sadler’s

murder, one of 58 in the city in 1999, shocked neighbors in this

quiet bedroom community which saw its homicide rate climb to a

five-year high. Sadler’s murder was one of the most chilling and

cold-blooded in recent memory.

Sadler’s

murder, one of 58 in the city in 1999, shocked neighbors in this

quiet bedroom community which saw its homicide rate climb to a

five-year high. Sadler’s murder was one of the most chilling and

cold-blooded in recent memory.

In

1999, the year of his murder, the number of homicides in the Taraval

police district spiraled to an unprecedented nine, up from five in

1998 and three in 1997.

Although

the identities of Sadler’s killers were known to police at the

time of his murder, no arrests have been made and the odds are that

his killers will never serve a day in jail for their crime.

According

to sources familiar with the case, several young Asian males,

identified as members of the Jackson Street Boys, a violent street

gang, were thrown out of the club earlier in the evening for

fighting and vowed to return for revenge.

Although

Sadler’s only involvement was to break up the altercation and calm

tempers down, he ended up paying with his life.

According

to witnesses, the young men returned to the bar about 1 a.m. in a

car and fired a weapon through a window. One man was wounded and

Sadler was hit in the chest. He died in the arms of his fiancée

before help could arrive.

Criminal

justice system riddled with problems, staff shortages

As

families of victims cry out for justice, what they often find

instead is an understaffed, underfunded, politically driven criminal

justice system that is working hard but failing to deliver closure

to grieving families.

In

addition to a backlog of unsolved cases and a short-staffed homicide

unit, the Crime Scene Investigations (CSI) team, a critical

component in the criminal justice system, is short six

investigators.

When

a homicide occurs, a central dispatcher calls a homicide team, the

coroner, an ambulance, and a member of the Crime Scene

Investigations team.

If

witnesses are not available, the coroner’s report, which

determines the cause and time of death, is often crucial to solving

a case.

The

CSI investigator is called to the crime scene to collect the

physical evidence that is routinely used by homicide officers to

identify suspects. Eventually, the district attorney uses the

evidence collected at the crime scene to build a convincing case in

court.

Members

of this team are seasoned veterans and many have years of special

training. It takes about 10 years before an officer has the rank and

seasoning to apply for a position on the team. In addition to

collecting physical evidence, investigators also take photographs,

make a diagram of the crime scene and process any finger and palm

prints.

This

summer the CSI team received a new $2.5 million computer system, the

Palmprint AFIS, that it hopes will make a serious dent in solving

all crimes, including homicides. The new technology allows an

investigator to scan palm prints into a system that searches for

matches in national and state data bases. Called “cold hits” by

police, the instantaneous matches provide police officers with

immediate suspects.

Since

palm prints represent about 30 percent of all prints found at crime

scenes, Jim Norris, the director of the Forensic Services Division,

believes the new technology will prove to be a good weapon for

solving homicides.

But

Norris says a biggest threat to solving homicides is the recent

retirement of seasoned investigators.

The

CSI team, which normally has 20 investigators, is down about 30

percent. Not only has the shortage led to a morale problem within

the unit, but Norris is concerned about compromising evidence.

Norris explained that if two homicides occurred at the same time,

the team is so understaffed it could not effectively respond.

“If

we had two serious homicide cases back-to-back we would have a

problem. It will compromise the evidence. There is absolutely no

question about it,” he said.

Crime

lab understaffed and underfunded

Once

the CSI team collects and secures physical evidence at a crime

scene, it is analyzed by criminalists in a new state-of-the-art

crime laboratory at the former Hunters Point Naval Shipyard.

Once

the CSI team collects and secures physical evidence at a crime

scene, it is analyzed by criminalists in a new state-of-the-art

crime laboratory at the former Hunters Point Naval Shipyard.

Prior

to 1999, the lab operated out of a dingy, ill-equipped room at the

Hall of justice. When the state refused to accredit the lab because

of its inadequacies, DNA evidence had to be shipped out to external

laboratories for analysis.

After

accreditation failed, city representatives acquired land from the

Redevelopment Agency and converted a building that was used as a

postal facility during the Gulf War into a new laboratory.

The

prior facility was not adequate to ensure that we would not

contaminate evidence,” explained Martha Blake, a senior

criminalist who oversees the laboratory.

The

new lab is equipped with the latest technology and is in the process

of getting its accreditation from the state. About one-half of the

police crime laboratories in the country are currently accredited.

At

the present time, the lab is operating with 17 civil service

criminalists, 4 of which hold the title of senior criminalist. Two

police officers are also assigned to the crime lab.

But

the crime laboratory, like the CSI team, is understaffed. The

situation is particularly critical with DNA and Blake says she could

easily use double the staff to process DNA evidence.

Even

though DNA evidence is critical in homicide cases, according to

Blake homicide officers routinely wait two to three months for DNA

to be processed. Blake says she runs into homicide officers at the

Hall of Justice all the time who ask when their DNA reports will be

ready.

“That’s

the biggest gripe I get around there,” she said.

Terry

Coddington, a criminalist at the crime laboratory who specializes in

firearms, says his unit also needs about twice the staff.

Last

June, the firearms division of the crime laboratory acquired a new

system that allows it to image cartridge cases, enter the

information into a national data base, and make “cold hits” or

matches. While Coddington is enthusiastic about the new technology,

he explained that his unit lacks the manpower to input data.

“Just

in terms of building up a data base — that’s what we are way

behind on. We could probably use twice the staff just to get the

data into the system,” Coddington said.

In

order to attract a quality staff and keep the professional staff it

now has, Blake wants more funds for training and for memberships in

professional organizations.

“Our

entire budget for professional training for the year is $5,000. The

city of Oakland pays for membership in two professional

organizations for its personnel — we don’t pay for one,” Blake

said.

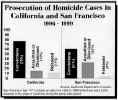

DA’s

low prosecution rate lamented by head of crime lab

Blake

leveled harsh criticism at the district attorney for failing to

prosecute cases, including homicides, where strong physical evidence

has been documented.

Blake

leveled harsh criticism at the district attorney for failing to

prosecute cases, including homicides, where strong physical evidence

has been documented.

“It’s

frustrating. We work hard to put together good evidence and they

often times don’t take risks. The DA’s office only wants to take

cases they can win,” she said.

District

Attorney Terence Hallinan, who has come under fire from the mayor in

the past for being lax on prosecuting violent crimes, declined to be

interviewed.

In

response to written question about Blake’s statement, Fred

Gardner, a public relations spokesman for Hallinan, wrote only, “We

have a different standard.”

But

Hallinan’s chief trial attorney, Linda Klee, says many factors

make homicide cases more difficult to prosecute. According to Klee,

a lack of witnesses in gang-related cases, understaffing, grants

that tie the agencies’ hands, the fact that homicides cases take

two to three years to prosecute, and liberal juries all contribute

to the problem.

Klee

said out of a staff of 120 attorneys only 30 to 35 handle a limited

number of cases over a longer period of time, which she called “vertical

caseloading.”

According

to Klee, short-staffing forces cases to bounce back and forth

between attorneys rather than on a district attorney handling most

of the case from beginning to end.

“We

need to do more cases vertically. We don’t’ have the resources,”

Klee said.

Because

homicide cases routinely take years to prosecute and the DA’s

office claims to be short-staffed, Klee says that five deputy

attorneys are assigned to homicide cases.

“When

motions start rolling in, it can take two to three years to trial,”

Klee said.

Police

department opts out of computer system

At

Mayor Willie Brown’s Crime Summit in March, figures were released

that show a 27 percent increase in the police department’s budget

from fiscal 1995-96 through 2000-01.

At

Mayor Willie Brown’s Crime Summit in March, figures were released

that show a 27 percent increase in the police department’s budget

from fiscal 1995-96 through 2000-01.

During

the same time period, the district attorney’s office received a

57.3 percent increase in its budget.

Part

of an increase in this year’s budget will be allocated to a new $4

million computer system to replace the aging technology now used by

the criminal justice community.

The

old Case Management System (7), which was considered revolutionary

in 1975, is so outdated that many criminal justice agencies are

developing their own internal systems, an act that threatens the

historically integrated model.

The

new system, called JUSTIS, would instantaneously link vital

components of the city’s criminal justice system, as well as

access information from state and federal systems, on one screen.

However,

several departments, including the police and sheriff, have declined

to participate in the project.

“Both

the sheriff and police are embroiled in bringing up their own

system,” said Dwight Hunter, the project director for the JUSTIS

system.

Hunter

explained that convincing San Francisco police officers to convert

to the new system was a hard sell. He said he believes that broken

promises in the past are one reason why the department decided to

work on its own system. Hunter also said part of the problem is

normal resistance to change.

“I

tried. We went to the police and asked them how we could design a

system that works for them,” he said.

According

to Hunter, the new system has major advantages over the old network

for everyone. He explained that the new system would allow police

officers to instantaneously access on one screen the entire criminal

history of a suspect, including state and federal information in

seconds, complete with graphics.

The

current system does not have direct links to the information and has

to be accessed by going in and out of different data banks. The new

system would have all information contained within a single

communications system.

“What

they are using now — it would make you weep,” Hunter said.

A

major hurdle the project still faces is funding. Hunter says that to

hook up everyone that wants the new system would cost the city more

than $5 million this fiscal year.

While

the city made a verbal promise of $4 million, Hunter was told that

$750,000 of that amount will not be available. Hunter says

the District Attorney’s Office, the Adult Probation Department,

and the Public Defender’s Office are expected to fully convert to

the new system this year.

Carol

Dimmick